By Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

The Hanoi summit is under a week away, Daily NK recently put out new market price data, and I’ve finally had time to update my dataset. There seems like no better time than the present to take a look at some of the numbers we have available for the North Korean economy, thanks to outlets such as Daily NK and Asia Press/Rimjingang.

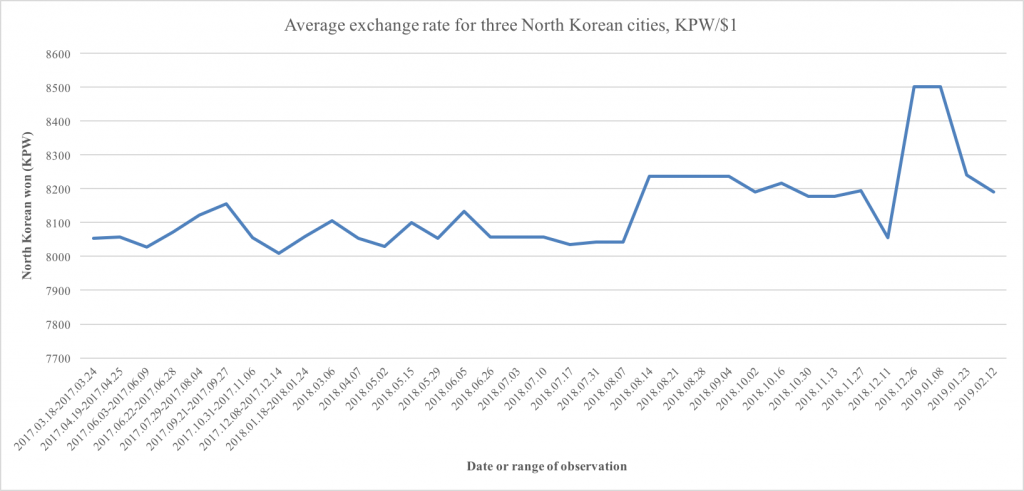

Currency

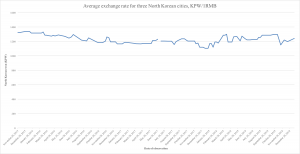

Let’s start with the exchange rate. A few weeks ago, the (North Korean) won depreciated quite significantly against the USD, which I wrote about here. At 8,500 won/1usd, the USD-exchange rate on the markets hit its highest point since the inception of “maximum pressure”. The graph below is shows the average market exchange rate in three North Korean cities for won-to-USD.

Graph 1. Average won-USD exchange rate on markets in three North Korean cities, spring of 2017–February 2019. Data source: Daily NK.

As the graph shows, the won rebounded somewhat after the initial spike in early January. According to the latest data point, the exchange rate stands at 8190 won, still somewhat higher than the average for the period, 8136, but barely.

What could have caused this spike? One possibility is that the government has started to soak up more foreign currency from the market, because the state’s foreign currency coffers are waning. After all, given the vast trade deficit, the continued necessity of spending hard currency on things like fuel (bought at higher prices through illicit channels to a greater extent) and other factors, it would make a great deal of sense. Currencies fluctuate all over the globe, sometimes based even on loose rumors that fuel expectations. One anonymous reader who often travels to North Korea for work heard from Korean colleagues that accounting conditions for firms had gotten stricter, likely because the government wants to be able to source more foreign currency from the general public.

It is also noteworthy that while the Daily NK price index reports that the USD-exchange rate has gone back to more normal levels, the Rimjingang index remains at very high levels. Its latest report (February 8th) has the USD at 8,500, and on January 10th, it registered 8,743 won, a remarkably high figure that the Daily NK index hasn’t been near since early 2015. The difference between the two may simple come from the figures being sourced from different regions, or the like. North Korea’s markets still hold a great deal of opportunity for arbitrage, not least because of the country’s poor infrastructure.

So, it does seem like there may be some unusual pressure on the won against the dollar. What it comes from is less clear, but the state demanding more hard currency from the semi-private sector and others may be one important factor. In any case, we shouldn’t be surprised if the trend continues, unless sanctions ease soon.

At the same time, while the RMB has appreciated against the won over the past few weeks, it hasn’t really gone outside the span of what’s been normal over the past few years.

Graph 2. Average exchange rate for won to RMB, average of three North Korean cities, late 2015–early 2019. Data source: Daily NK.

The average exchange rate for RMB since the start of Daily NK’s data series in late 2015 is 1228 won. The latest available observation gives 1241 won/RMB, and the RMB has appreciated against the won over the past few weeks. The Rimjingang data, here, too, gives a higher FX-rate for RMB than Daily NK, at 1250 won. Their index, too, shows the FX-rate for RMB going up over the past few weeks, but not to levels out of the ordinary. Still, if the won continues to depreciate against both the dollar and the RMB, it may be a sign of a more persistent foreign currency shortage.

Food prices

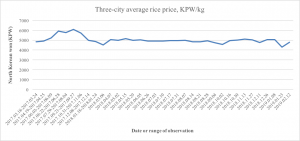

Rice prices remain as stabile as ever, in fact, even more so than this time last year. They continue to hoover between 4,500–5,000, with the latest observation being at 4,783.

Graph 3. Average rice price for three North Korean cities, spring of 2017–early 2019. Data source: Daily NK.

This should not necessarily be taken to mean that North Korea’s current food situation is not problematic. Even with increasing harvests in the past few years, it’s always been fragile. The past year’s drought reportedly took a toll on the harvest. Though market prices aren’t suggestive of any shortages as of yet, that could change in the months ahead. The latest harvest was likely lower than those of several previous years and difficulties in importing fertilizer may have contributed, but the dry weather was the main factor.

Even with a slightly lower harvest than in previous years, it seems that structural changes in agricultural management has improved agricultural productivity to such an extent that food safety isn’t severely threatened even with a reduced harvest.

Gasoline

Gas prices appear to have stabilized around a sanctions equilibrium, of sorts, since a few months back. The past year hasn’t seen any spikes near those of the winter in 2017, when prices went above 25,000 won per kg. For the past year, the price has mostly hovered between 13,000 and 15,000 won per kg. The last observation available from Daily NK, is at 15,200 won per kg. This is slightly higher than the average of the past 12-month period, 13,500 won per kg. A more recent report from Rimjingang puts prices at 13,750 won per kg, so perhaps prices have declined over the past few weeks.

What’s likely happened is that China has settled on a comfortable level of enforcement of the oil transfers cap, for now. (For a detailed look at fuel prices in North Korea and Chinese sanctions enforcement, see this special report.)

Graph 4. Average gasoline price, three North Korean cities, early 2018–winter 2019. Data source: Daily NK.

There is lots to be said about gas prices and their impact on the economy, but for now, it looks like supply of gasoline in North Korea is restricted, but stabile.

Hard currency reserves

I unfortunately don’t have any data to present on this issue, but it’s too important not to mention. We don’t know how large North Korea’s foreign currency reserves are, but all throughout “maximum pressure”, people have been speculating that they’ll soon run out. One South Korean lawmaker said in early 2018 that by October that year, North Korea would be out of hard currency. That clearly didn’t happen.

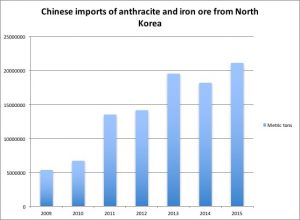

The lack of stabile foreign currency income may still be a problem for the regime, as mentioned above. It’s hard to imagine how it couldn’t be a huge headache. Look at the following graph for example, showing North Korea’s trade (im)balance with China, throughout 2017 and the first few months of 2018.

Let’s assume that China is simply letting North Korea run a trade deficit, with only some vague future promise of payment in the form of cheap contracts for coal and minerals. Or, let’s say that China is even just sending North Korea a bunch of stuff without requiring any form of payment whatsoever. It seems highly unlikely to me that even a government like China would support the full extent of these imports. Even if North Korea is only paying in hard currency for a relatively small proportion of what it imports from China, that’s still a lot of money that’s just leaving the vaults, with virtually nothing coming in to replenish them. How long can this go on for? Probably longer than many estimated at the onset of “maximum pressure”, but certainly not forever.

Summary

In sum, judging by the numbers, North Korea’s domestic economic conditions appear stabile but quite difficult. No sense of widespread, general crisis is visible in the data. Nonetheless, the regime is likely under a great deal of stress concerning the economy. How much is hard to tell, but definitely enough for some form of sanctions relief and/or economic cooperation to be high on their agenda for Hanoi.