Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein

China and North Korea opened a new border crossing over the Yalu River, signaling aspirations for deeper economic ties between the neighbors even as Pyongyang’s trade remains crimped by international sanctions.

The border checkpoint at the foot of a new bridge opened Monday, connecting the northeastern Chinese city of Jian with North Korea’s Manpo, Chinese state media reported. The China-DPRK Jian-Manpo highway connection is for passenger and cargo transport and hosts an advanced customs facility, the China News Service said.

The opening was marked by several tour buses crossing from the Chinese side and then returning from North Korea, the Yonhap News Agency of South Korea reported, citing a person familiar with the matter. The ceremony appeared to show that local Chinese officials were ready to step up trade and exchanges with North Korea in response to its call for economic development, according to Yonhap.

China provides a lifeline to North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and his state has long been dependent on Beijing’s help to keep its meager economy afloat. Kim’s summit with U.S. President Donald Trump in Hanoi broke down on Feb. 28 over sanctions that have cut Pyongyang off from global commerce and were imposed on North Korea for its pursuit of a nuclear arsenal.

It was unclear how the new border checkpoint — the fourth between China and North Korea — would operate under the sanctions, which ban or limit a broad range of goods from moving in or out of the country. The South Korean Unification Ministry declined to comment.

The economic penalties are expected to be a main topic of discussion when South Korean President Moon Jae-in meets Trump at the White House on Thursday. Moon, a long-time advocate of reconciliation with North Korea, has repeatedly played the role of mediator since he took office in May 2017 amid escalating threats of war between Trump and Kim.

The Manpo border area has drawn the attention of North Korea for years, with Kim’s father and former leader, Kim Jong Il, crossing there in 2010 in one of his rare trips outside the country, the Chosun newspaper of South Korea reported at the time. In the 2010 trip, Kim Jong Il visited the school his father and North Korean state founder Kim Il Sung attended on the Chinese side when he was a child.

China and North Korea agreed to embark on the bridge project in 2012 and completed construction in 2016, Yonhap reported. The opening was delayed by UN Security Council sanctions imposed on North Korea.

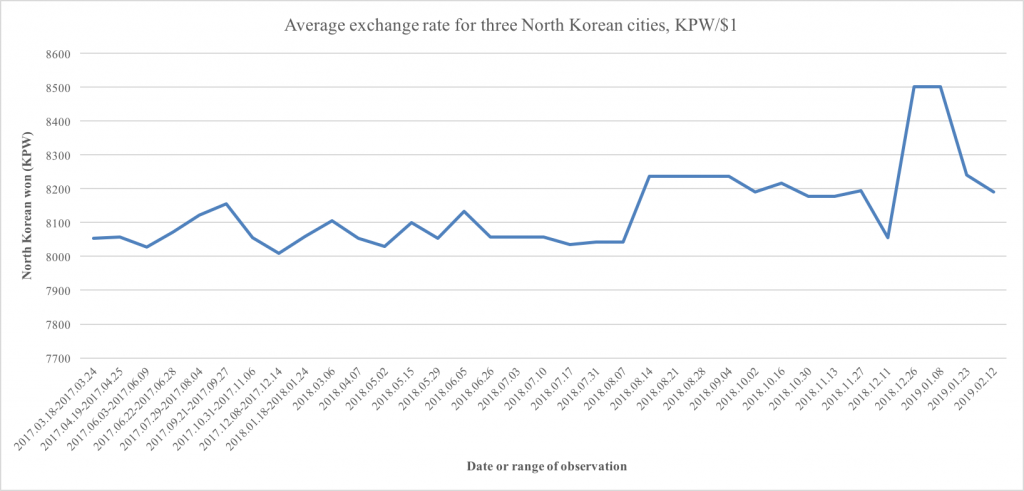

In 2017, China’s overall trade with North Korea declined by more than 10 percent to about $5 billion, as Trump secured Beijing’s backing for four escalating rounds of sanctions in response to North Korea nuclear weapons program testing.

China, North Korea Open New Border Crossing Despite Sanctions

Jon Herskovitz and Dandan Li

Bloomberg News

2019-04-08

China and North Korea on Monday officially opened a new cross-border bridge halfway along the Yalu River, offering clues to their possible expansion of bilateral economic exchanges amid ongoing international sanctions.

The new bridge connects Jian in the northeastern Chinese province of Jilin with North Korea’s northern border city of Manpo.

The two countries agreed to the Jian-Manpo bridge project in May 2012 and completed its construction in 2016. But they have since delayed its official opening, apparently affected by United Nations Security Council sanctions on the North over its missile and nuclear programs.

Jian, located about halfway along the Yalu River, is considered a representative base of trade between North Korea and China, along with Liaoning Province’s Dandong on the Yalu River estuary and Jilin Province’s Hunchun on the Tumen River estuary.

Four tourist buses arrived in China from North Korea via the new bridge at 8:20 a.m. Monday before returning to the North about one hour later carrying about 120 passengers.

According to a local tour company, the tourists are planning to return to Jian around 5 p.m. after visiting attractions in and around Manpo.

A source in the border area told Yonhap News Agency that China’s provincial governments appear to be boldly trying to cooperate with North Korea in response to their demand for economic development.

“North Korea’s denuclearization has not been implemented, but the environment surrounding North Korea and China appears to be partially changing,” the source said.

“China may not expand its economic cooperation with North Korea considerably in consideration of its relations with the United States. But the opening of a new bridge may signal expansion of bilateral economic exchanges,” said the source.

Article source:

China, N. Korea open new cross-border bridge

Yonhap News

2019-04-08