Daily NK

Kim Min Se

7/20/2007

A newsletter published on the 18th by “Good Friends” a North Korean aid organization claimed that “On average 10 people die of starvation throughout North Korea.”

However well informed North Korea defectors and North Korean tradesmen who travel to China refute the organization’s claim and argue, “It would be difficult for that to happen.”

The organization published in its newsletter, “Since the end of June, starvation has been occurring in each province throughout North Korea” and informed, “The number of people dying in North Pyongan, Yangkang, Jagang, South and North Hamkyung continues to rise everyday.”

In particular, Good Friends stated, “In South and North Hamkyung, about 10 people are dying of starvation in each city and province” and “On the whole, the people dying are aged 40~65 years.”

“Though the cause behind the deaths is different for each person, most of the complications are related to malnutrition” informed Good Friends. They added, “A mass famine has not yet begun, however authorities and people feel the threat of the situation” stressing the urgency of North Korea’s food crisis.

An affiliate of Good Friends said, “Presently, only 20,000 tons of South Korea’s food aid is offered (to North Korea)” and commented, “This rate of aid is too slow in saving the lives of the dying people.”

However, there are criticisms against this claim. Some argue that Good Friends had excessively inflated North Korea’s food crisis.

Choi Young Il (pseudonym) questioned this claim by Good Friends after a telephone conversation with his family in North Korea on the 16th. He said, “Even up to two days ago, I spoke to my family on the phone but they didn’t mention anything about a food crisis.”

Moreover, Choi said, “Alleging that about 10 people on average are dying in the cities and province of South and North Hamkyung is no different to saying that nearly 400 people are dying throughout the whole region of South and North Hamkyung every day” and added, “In that case, this is similar to the early period of mass starvation in the early 90s.”

“Only looking at North Hamkyung, most of the people living in the border regions live off illegal trade through China and though they may not be living well, I was aware that they got by without having to eat porridge” Choi said and remarked, “I don’t believe the claim that 10 people are dying of starvation every day.”

On the same day, Hwang Myung Kil (pseudonym) a North Korean citizen who came to Yanji to visit his relatives in China said in a telephone conversation with a reporter, “I cannot believe the rumor that people are starving to death around the border areas of the Tumen River” and commented, “I haven’t even heard stories of more people starving to death in the mines and they live in masses around Musan.”

Hwang said, “Even amongst the people in Musan, there are only a small number of people who live off corn for three meals a day… Nowadays, people look for quality rather than quantity.” Further, he said “Though life is tough, people have found their own way of survival. It’s not to the point of starvation.”

If according to Good Friends, 10 people are dying on average due to starvation, this situation would indicate signs similar to the mass starvation in the early 90s. However, the cost of rice claimed by Good Friends clashes with their claim.

When North Korea faced their mass crisis in the mid-90s, the cost of corn rose dramatically. In October 1995, 1kg of corn cost 16won, but this doubled to 30won. However, there has not been much change to the cost of food in North Korea.

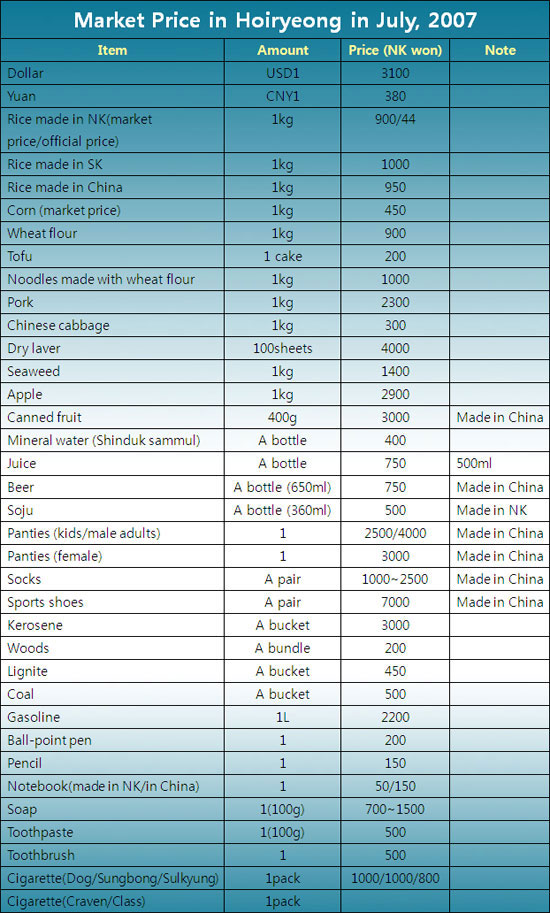

According to a recent survey by the DailyNK on the cost of goods in North Korea’s Jangmadang (markets), 1kg of corn rice at Hoiryeong markets sells for 450won and 1kg of rice produced in North Korea costs 900won.

More importantly is the cost of cigarettes. A packet of Sunbong, a North Korean brand of cigarettes sells for 1,000won and “Cat” cigarettes for 1,300won. The cost of a kilo of rice is still cheaper than a packet of cigarettes.

If North Korea’s starvation was on the brink of a massive food shortage, then it is expected that the cost of rice and corn would escalate dramatically as an onset to the crisis.

On the other hand, Kim Il Joo (pseudonym) a Chinese tradesman and expert on North Korean markets said, “I can’t say that North Korea’s food situation is smooth, but I don’t think it will get any worse than this.” Kim said “Now you can eat new potatoes and soon new corn will be available on the markets” and added, “Then, I think we will be able to get through another year.”

Deaths from hunger rise across N. Korea: civic group

Yonhap

7/18/2007

A growing number of people have died of starvation across North Korea since late last month, a South Korean civic group working to defend rights of North Koreans said Wednesday.

“Famine-driven deaths began to occur across North Korea in late June,” Good Friends said in a commentary carried in its weekly newsletter. “In some cities and counties in the provinces of North Pyongan, Ranggang, Jagang and South and North Hamkyong, the number of deaths is on the increase daily.”

In North Hamkyong Province, a daily average of ten people, mostly those aged between 40 and 65, died of starvation, the group added.

“The leading cause of death varied for each case, but most people are dying of famine-driven malnutrition and its complications,” the commentary said.

The price of rice rose steadily this month, with North Korea facing a crisis of massive deaths from hunger, it said.

The group then called on the Seoul government and the international community to send more emergency food aid to help North Koreans, especially through the just-reconnected cross-border railways.

In mid-May, the two Koreas conducted the historic test of the railways, reconnected for the first time since the 1950-53 Korean War. But it remains unclear when regular train service might start.