Daily NK

Kim Min Se

10/26/2007

There is a prospect of the rise of “second food crisis” next year because of the flood disaster and the resulting food shortage.

A senior researcher at Korea Rural Economic Institute, Kwon Tae Jin said warningly, “Unless North Korea comes up with a special plan to secure food supply, there will come another food crisis next year, which is as severe as the one in the mid and late 1990s.”

Kwon anticipated that North Korea would need 5.2 million tons of grain for domestic consumption. Unfortunately, it is expected that North Korea would produce around 3.8 million tons of grain. This means there will be a shortage of 1.4 million tons of grain.

The statistics indicates there is a real possibility of a food crisis. North Korean authorities announced that the flood inundated about 2.2 billion ㎡ of farmland, which accounts for 14 percent of the country’s farmland. It is estimated that 2.2 billion ㎡ of farmland produces at least 500,000 tons of grain.

However, another prospect says that although food shortage is inevitable, it will not lead to mass starvation in North Korea as it did in the mid-1990s. Most of defectors from North Korea said, “Since the mid-2000s, things have changed. There won’t be any serious starvation.” They said that the current situation is different from that of those days under the central food distribution system. They added that the Jangmadang (markets) economy has changed a way for life among North Korea people.

◆ The amount of demand for food is overestimated

It should be double-checked whether North Korea really needs a minimum of 5.2 million tons of grain. There is criticism that the estimate of food demand which was calculated by some South Korean experts on North Korea and relief organizations is unrealistic. It is also pointed out that the estimate is calculated based on the nutrition standard of South Korea.

Defectors said that mass starvation would not have occurred if North Korea had at least a half of 5.2 million tons of grain in the mid 1990s.

Although the international standard for daily nutritional intake is between 2,000 and 2,500 kcal/day, North Korea sets the standard at 1,600 kcal/day, which amounts to 450 grams of grain.

It is easy to estimate the minimum amount of food demand needed in North Korea. Let us say every individual including children and the elderly needs 550 grams of grain per day, which is equal to the daily amount of food distributed to every adult by the state. With the population of 22 million in North Korea, the country then needs 12,100 tons of grain each day and 4.4 million tons of grain per year.

It is known that the North Korean government provides 550 grams of grain for adults and 300 grams for both children and the elderly. According to CIA’s World Fact Book 2004, the population aged between 15 and 64 in North Korea is around 15 million, which accounts for 67.8 percent of total population. This means the population of children and the elderly together reaches about 7 million. If we do the math, we come into conclusion that the amount of food needed in North Korea every year is 3,777,750 tons of grain.

Recall that North Korean people had received the aforementioned amount of food through the state food distribution until early 1990s. Of course, the country did not suffer from mass starvation back then.

The mass starvation during the mid-1990s resulted from huge decrease in food production between 1994 and 1998. In those years, North Korea produced about 2 million tons of grain, which fell far below the needed levels of food production. Hwang Jang Yop, former secretary of the Worker’s Party also testified that in the fall of 2006, while he was still in North Korea, he once heard the secretary of agriculture Seo Kwan Hee worrying about extremely low food production.

Therefore, it is correct to estimate the minimum amount of food needed in North Korea at 3,777,750 tons of grain. If the food production decreases below 3 million tons, then the food prices will skyrocket, and the possibility of mass starvation will be increased.

◆ A New way of life among North Korean people helps prevent them from falling victim to starvation.

North Koran people do not believe in the state authorities any more. The people know that they suffered from horrible starvation because they relied on the state and its food distribution system. During the crisis, many people had desperately waited for food to be distributed until they collapsed and died. Nowadays, North Korean people find a means of living by themselves at Jangmadang.

“There is no free ride” is the words on everybody’s lips in North Korea, which means that everyone must work hard in order to make a living. The lowest class became a day laborer.

The mass starvation of the mid-1990s has brought a significant change into North Korean society. Except a few, most of North Korean people do not rely on the state’s food distribution system. Instead, they have come up with a variety of survival techniques such as engaging in business, illegal trade with China or real estate transactions, receiving support from defected family members, and house sitting.

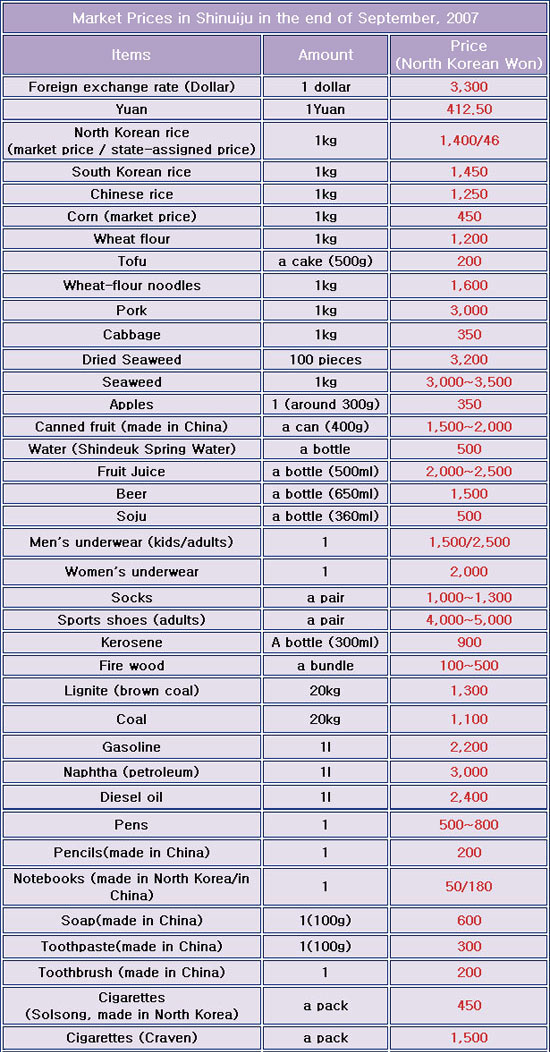

In that manner, North Korean people make money and use it to buy rice. An affiliate at the Bank of Korea who studies price trends of North Korea said, “Since the adoption of the July 1 Economic Improvement Measure, the price of rice and corn has increased the least.” If the prices go up, people would tighten their belts and decrease their spending on every item except rice. This means they are not that vulnerable to starvation as they used to.

◆ Businessmen are good at securing food.

Recently, a number of rich businessmen have emerged. Some have tens of thousands dollars, and others as many as several million dollars. Groups of Jangmadang businessmen have been organized with these rich businessmen as the leaders.

These businessmen come and go to China as they please and supply food and goods to Jangmadang in North Korea. If the rice price in North Korea is expensive than in China, they buy Chinese rice and sell it at Janmadang. In this way, they help balance supply and demand at the market.

Furthermore, Chinese residents in North Korea and Chinese businessmen also joined the North Korean businessmen as providers at the market. They too sell food produced in China at Jangmadang when food prices go up in North Korea. If possible, they even sell rice reserved for the People’s Army. There was an accusation that the state authorities supplied food aid from overseas for the People’s Army while collecting food produced in North Korea at the same time.

Of course, some businessmen could deliberately keep a hold on food supply anticipating an increase in food prices. However, that kind of unfair activity is temporary. Although it is too early to tell, the “invisible hand” of the market, however small it is, is operating in North Korea and acting as a preventive measure against starvation.