Nautilus Institute Policy Forum

Policy Forum Online 10-027A

5/12/2010

Alexander Mansourov

North Korea is not static and inflexible. Indeed, there tends to be a very dynamic picture once you look below the surface. Change is a constant but, as in almost any state or society, it brings about tension. However, there is little or no sign that current tensions, caused by changes in the distribution of power within the leaderships’ core cadre, positioning for succession, or economic reforms are eroding the overall strength of the regime. While such tensions may spill over into society, there have been no signs that they have risen to a level that significantly weakens the regime or have made it feel that drastic action is needed.

Contrary to the popular view, North Korea is not being torn apart by an epic battle between the state and markets. The two have over time established an uneasy but symbiotic relationship. The state still considers the markets as parasites and vice versa, but each has learned to exist with the other. The popular argument that the reopening of markets in the North after their alleged (but unverified) closure is a sign of government capitulation before their power is not persuasive.

Much of the “evidence” we have for the latest uptick in internal tensions following the currency redenomination consists of recycled stories from unproven or unreliable sources relating anecdotes from small slices of the country. These publicly available sources for North Korea are very subjective and come through the lens of defector groups and humanitarian non-governmental organizations that, quite frankly, have their own agendas. Corroborating these reports is often impossible. Separating speculation from rumor and fact is difficult. The best we can do is to strip back some of the speculative veneer and establish hypotheses we can test over time.

What is Really Happening?

In spite of recent speculation in the New York Times and other Western media about North Korea’s growing economic desperation and political instability, Pyongyang is, in fact, on a path of economic stabilization. Last year’s harvest was relatively good-the second in a row-thanks to a raft of developments including favorable weather conditions, no pest infestations, increased fertilizer imports from China, double-cropping, and the refurbishment of the obsolete irrigation system. Thanks to the commissioning of several large-scale hydro-power plants which supply electricity to major urban residential areas and industrial zones, North Korea generated more electricity in 2009 than the year before, although losses in the transmission system remain significant.

According to China’s Xinhua news agency, industrial production in North Korea grew by almost 11 percent last year and 16 percent in the first quarter of 2010, compared to the first quarter of 2009. That positive development was facilitated by two nationwide labor mobilization campaigns-the “150-day campaign” and “100-day campaign” as well as growth in extractive industries, construction, a revival of heavy industries, modernization of the consumer-oriented industries and the expansion of the high-tech sector, especially, information and biotechnology.

Despite a decline in inter-Korean commerce and international sanctions imposed after the North’s missile and nuclear tests in early 2009, foreign trade did not contract in any meaningful way thanks to burgeoning ties with China. Moreover, Beijing seems to be committed to dramatically expanding its direct investments in the development of the North’s infrastructure, manufacturing, and service sectors.

There is no question that, for ideological, political, and national security reasons, North Korea’s macroeconomic policy has always been oriented towards the needs of domestic producers. The requirements of large-scale munitions and heavy industries have been the top priority, an orientation that has handicapped the development of domestic consumer-oriented industries. Since the collapse of the government-run, public food distribution system in the 1990s, Pyongyang has largely neglected the interests of individual consumers. It has allowed inflation to eat away at their disposable income, leaving them with only a few possible coping strategies. Those strategies have included pilferage of state assets, official corruption and participation in emerging retail markets where quasi-private merchants have been trading mostly in domestic agricultural produce and Chinese manufactured goods.

As the state-owned economic sector began to recover in the past two years, it had to confront labor shortages, rising production costs, and a powerful competitor-China. Whereas the extractive industries (especially coal and ore mining) benefitted from skyrocketing global raw materials prices as well as proximity and access to the ever-hungry Chinese market, the manufacturing industries hit the “Great Chinese Wall” of cheap consumer goods and industrial products that flooded the country. The competition was killing North Korea’s domestic manufacturers, who had barely begun to recover from two decades of depression.

At the same time, the North’s consumers-always conscious of rampant inflation-dodged mandatory savings requirements and began to increase consumption. They started to develop a clear preference for spending their meager disposable incomes on foreign-made goods in the newly emerging farmers’ and general industrial markets rather than in state-owned stores. Insensitive to the plight of the domestic industries, consumers voted with their purses for better quality, albeit more expensive, imports.

In addition, this development helped drain liquidity from the state banking system. Since the post-July 2002 economic reforms, salaries and money earned by private merchants were rarely deposited in bank accounts and returned to regular state banking channels. Instead, they circulated in emerging markets, were stored in kimchi jars, buried underground, or exchanged for renminbi or euros and taken out of the country by foreign (mostly Chinese) traders. Despite the Central Bank’s proclivity to print more money to increase the supply needed for state investment (which in turn fueled inflation), industrial producers were confronted with increasing difficulty in procuring investment funds from the state banking system, which was running short on previously mandatory individual bank deposits.

Rationale for Current Macroeconomic Stabilization Measures

In formulating the current round of measures, the authorities had to figure out how to cut a political, economic and social Gordian knot. Their options were restricted by an uncertain leadership agenda, ideological confines, political biases, lack of extensive macroeconomic stabilization experience, and scarce resources.

First, they had to reconcile the interests of domestic producers, very well represented by senior managers of state-owned enterprises at all levels of state power, otherwise known as the red directorate, who pressed the government to lower their rising production costs and to protect them from foreign (Chinese) competition. At the same time, consumers, asserting themselves through the nationwide structures of people’s committees and public organizations, sought higher salaries and alternative employment in the non-state sector, with a preference to consume higher quality imports.

Second, they had to reconcile the interests of state bankers-who were urging modernization and re-capitalization of the state banking system in the throes of an unprecedented credit squeeze-with those of the general population worried about inflation, mistrustful of the system, and reluctant to keep their savings in banks.

Third, they needed to find a way to repay the people’s life bond funds “borrowed” from the population in 2003 while also mobilizing additional funds for future capital investment even through confiscatory measures.

Fourth, they probably wanted to restore public confidence in the national currency and must have been motivated by a desire to combat inflationary expectations as well as to signal that inflationary days were over.

Fifth, they probably wanted to curb the growing influence of the new moneyed class demanding fewer restrictions on its businesses and foreign exchange transactions, while placating the regime loyalists, who still believed official propaganda and defended the advantages of the socialist economic system.

Sixth, they wanted to restore the credibility of the state-centered economic management system as demanded by the anti-market neo-conservatives from the party establishment. At the same time, policy-makers wanted to restrain the ever-present bureaucratic class seeking to control, license, and regulate anything and everything, which gave rise to rampant official corruption.

Finally, they wanted to re-assert monetary sovereignty since growing foreign currency substitution was undermining the central bank’s control over the money supply. The loss of monetary sovereignty would have become an insurmountable practical obstacle to building a “strong and powerful state” by 2012, North Korea’s publicly stated objective, and could not be tolerated politically, especially during a leadership transition period.

In an interview with Kyodo News on April 18, 2009, Ri Ki Song, economics professor at the Economic Institute of the Academy of Social Sciences, a North Korean government think tank, pointed out that “redenomination was intended to curb inflation, enhance currency values and create a favorable environment for economic management, and it was also aimed at stabilization and improvement of the people’s livelihood by supplying goods through a systematic national distribution system.”

Outlines of the New “Package Deal”

The currency redenomination began to unfold in late 2009. In November, the Supreme People’s Assembly (SPA) Presidium issued a decree “On Issuing New Currency.” At the same time, the Cabinet of Ministers promulgated two decisions entitled “On Stabilizing People’s Livelihood” and “On Establishing Proper Order in Economic Management System.” These were quickly followed by a series of new regulations issued by the Central Bank, Ministries of Finance and Commerce, Price Regulation Bureau, General Bureau of Customs, and other government agencies.

The purpose of these initial steps appears to have been two-fold. First, the North wanted to reinvigorate domestic production of consumer goods. That would be done through import substitution as well as rebuilding the purchasing power and stabilizing the living standards of the mass of budgetary employees. The livelihood of these people-who constitute the overwhelming majority of the workforce, are employed at institutions such as state-owned industries, hospitals and schools and are paid out of the state budget-had been gradually eroded by marketization and high inflation. Second, the reform was designed to encourage savings as well as induce cash flow from proliferating black markets to the state banking system, which had been rapidly losing its handle on money in circulation.

While this move has been portrayed in much of the Western media as a “failure” that has caused significant tensions inside the North, in fact, it is too early to declare these measures either a failure or success. Such redenominations are almost always a source of tension when they are carried out in any country and often need to be adjusted or implemented again before achieving the intended results. North Korean economist Ri Ki Song admitted that “Price adjustments and other related measures were not implemented quickly enough, and there was a situation where [North Korea] could not open the market for several days.” But he took issue with “some Western reports that did not reflect what actually happened.” Ri noted that “In the early days immediately after the currency change, market prices were not fixed, so markets were closed for some days, but now all markets are open, and people are buying daily necessities in the markets.”[1] If inflation is eventually tamed and the currency exchange rate stabilized in the long run-the verdict is still out on both accounts-then these measures may eventually be viewed as a partial success.

As always, there were winners and losers but, once again, the reality appears to be somewhat less clear-cut than has been assumed by the Western media, economists and other analysts. In view of the ongoing preparations for the leadership succession, the redenomination could be viewed as a populist measure aimed at inflicting pain on less than 10 percent of the population through wealth redistribution in order to win support from more than 90 percent of the population who still live on state salaries and have not seen any improvement in their life despite burgeoning market activities. North Korea is still fundamentally a socialist society, and Kim Jong Il’s regime probably won some measure of support from the vast majority of North Koreans for its crackdown on corruption and abuses by rich traders and corrupt government officials who benefitted the most from bustling activity in black markets.

Private merchants may have felt some pain (although likely had stored their wealth in goods, commodities or foreign exchange rather than the old North Korean currency). But the heaviest losses appear to have been suffered by corrupt low and mid-ranking officials from the “power organs” (People’s Security and State Security officers as well as officials from courts and prosecutors’ offices) and government bureaucrats who wielded licensing, auditing, or controlling authority at the county and provincial levels. They had allegedly accumulated substantial savings through bribes and abuse of power and kept their ill-gotten gains in kimchi jars and under the mattresses at home. As a result, these officials could not find a way to get these stacks of old banknotes exchanged for new ones. According to a knowledgeable South Korean source, it is their money that was reported floating in sacks down the Yalu River after redenomination, not the traders’ capital. In short, the currency move may have ended up as more of a strike against corrupt officials and local elites rather than private traders. With markets re-opening and private trade resuming in late January, the latter rebounded fairly quickly, whereas it is likely to take a long time for the corrupt mid-level bureaucrats to recoup their losses through a new round of bribes and extortion.

In Ri Ki Song’s judgment, “an unstable situation occurred temporarily and partially after the currency redenomination,” but, “it did not lead to social chaos at all, and the unstable situation was quickly brought under control.”[2]

Following the currency redenomination, the next government move was to reset the official prices for commodities, such as grains, meats, and fuel, manufactured goods including textiles and daily necessities, and real estate use and utility fees to the pre-2002 level. Salaries of employees in the state sector of the economy were also adjusted, but at a much higher level. Reportedly, those who previously were paid up to 3,000 old won per a month saw an average 8 percent raise in their salaries, whereas those who used to receive a salary of more than 3,000 old won per month saw a decrease on the average of 10 percent per month. Farmers in the cooperative sector were reported to have received a one-time cash payout from 50,000 to 150,000 won in new money. These economic measures initially increased the purchasing power of most consumers in the country, especially those who depended solely on state salaries and wages for their income.

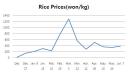

Even according to the Seoul government, the DPRK’s market prices and currency exchange rate appear to be stabilizing after predictable fluctuations from the surprise government-led currency redenomination last year. In its latest report on North Korea submitted to the National Assembly’s foreign affairs committee, the Unification Ministry said that market prices in the country were on a “downward path” following recent measures by the authorities. A kilogram of rice, which cost around 20 DPRK won immediately after the revaluation, soared to 1,000 won in mid-March but dropped to the 500-600 won range in early April, according to the ministry.

Furthermore, the North Korean government released another broadside of legislation in December and January: the Presidium of the Supreme People’s Assembly revised a number of laws pertinent to economic management ranging from those governing real estate management and commodities consumption to general equipment import, labor accounting, agricultural farms, water supply, sewage, and ship crews. These measures were aimed at bringing the existing regulatory framework in line with the new realities of an emerging market economy, where a growing number of corporate and private interests compete for access to and use of public assets. For example, the Real Estate Management Law is aimed at restructuring existing regulations for the use of public lands, especially for corporate and private purposes, and strengthening the ability of the state to collect real estate taxes and land use fees. It also stipulates the new right to grant “long-term land leases” to foreigners, which is especially important in promoting foreign investment in special economic zones such as Rason and Kaesong.

In January, the North’s Foreign Trade magazine unveiled the contours of the new tariff system established in accordance with the latest revisions in the regulations for the implementation of the DPRK Customs Law and the provisions of the Customs Law. In addition, late last year Kim Jong Il reportedly authorized the restructuring of the foreign trade management system, expanding the prerogatives of general trading companies and upgrading the status of special economic zones, in hopes of boosting domestic production of the export-oriented goods, encouraging import substitution, and attracting foreign investment in the consumer goods sector.

Also in January, the North Korean authorities revealed their intention to seek foreign investment and to reform the state banking system by establishing the second tier of quasi-commercial banks-the State Development Bank, Export-Import Bank, and State Science and Technology Fund-backed partially by the Central Bank and partially by foreign capital.

The stated goals behind this innovation in banking policy are to create favorable financial conditions for the implementation of a 10-year economic infrastructure development plan and five-year science and technology development plan, as well as to facilitate further expansion of foreign trade. The first plan envisions the implementation of six major projects-the development of food production, modernization of railways, construction of roads, expansion of ports, modernization of electric power grid, and development of the energy sector-within the next ten years, to be funded outside the regular state budget channels, primarily relying on Chinese venture capital. The five-year plan stipulates an increase in the state’s investment in science and technology as one of the pillars for a “prosperous, powerful nation,” with a focus on information technology, nano technology and bioengineering.

The notion that all of the measures announced in December 2009 and January 2010 were a hurried response to negative public reaction to problems in the currency revaluation is a little hard to accept. More likely, these were part of a longer-term development strategy of which the currency measures were only one component.

To sum up, North Korea is changing. The latest demonstration of the government’s desire to facilitate change is the new package of economic adjustment measures. Those measures seek to displace imports, restore self-reliance, and consolidate state control over the economic system at the expense of the newly emerging proto-markets in retail trade and the small private merchant class that may create political headaches for the regime down the road.

Subsequently, we may see the establishment of a new-more protectionist and statist-equilibrium in the relationship between domestic producers (industrial factories and plants), importers (trading companies), financiers (state bankers and foreign capital), and consumers (state retail industry and private markets). This might involve the government’s efforts to further control the demand, regulate the supply of imported goods through selective protectionist tariff measures, raise funds for new infrastructure and facility investment, boost the supply of domestically manufactured goods and make them more competitive and affordable.

How this will all work out remains to be seen. Whether the new equilibrium will facilitate economic growth and contribute to increasing production, trade, and consumption, or end up in economic failure causing social chaos and political instability is obviously the core question. Contrary to the rampant, often inaccurate speculation in the Western media, it’s much too soon to tell.